PSYCHO (Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1960, 2. & 9.11.) Graphic artist Saul Bass set new standards in the design of title sequences, who often worked together with his wife Elaine Bass and mainly did title design for the films of Otto Preminger and Alfred Hitchcock. The title sequence of PSYCHO combines abstract graphic elements with writing. Horizontal bars cut up and fragment the titles, until they can finally be properly read and thus point to the psychological fractures that scar psychopathic protagonist Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), who murders passing traveler Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) under the shower in his motel in the infamous scene.

DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN (Wings of Desire, Wim Wenders, West Germany/France 1987, 2. & 4.11.)"When the child was a child..." Instead of the opening credits, Wenders' homage to divided Berlin begins with a writing scene that fills the screen. Only during the course of the film can one attribute the hand, writing, and voice later deployed to one of the protagonists, the angel Damiel. At first, the words on paper create a transition from the book to the film and mark its literary memory which doesn’t only reveals itself again at the end of the film. In the meantime, we accompany the angels Damiel (Bruno Ganz) and Cassiel (Otto Sander) in their wanderings through 1980s Berlin.

ABSCHIED VON GESTERN (Alexander Kluge, West Germany 1966, 3. & 15.11.) Kluge's programmatically titled feature debut is about a young Jewish woman called Anita G. who emigrates from East German to West Germany. Lawyers and probation officers try to educate her, yet she soon finds herself on the run once again. Numerous intertitles interrupt the sober, distanced. and at times ironic portrayal and pass razor-sharp commentary on social conditions in West Germany – “Truth, when it appears seriously, is struck dead”.

SO IS THIS (Michael Snow, Canada 1982, 6.11.) “The film is a text in which each shot is a single word, tightly-framed white letters against a black background. With formalist belligerence, SO IS THIS threatens to make its viewers ‘laugh, cry, and change society,’ (…) Snow manages to de-familiarize both film and language, creating a kind of moving concrete poetry while throwing a monkey wrench into a theoretical debate (is film a language?), that has been going on for 60 years.” (Jim Hoberman) SO IS THIS is showing in a program with ZORNS LEMMA (Hollis Frampton, USA 1970, 6.11.) A classic of structuralist cinema that takes its title from a lemma in set theory named after German-US mathematician Max Zorn. The film "exemplifies the transition from alphabet-based thinking to cinematic thinking, in the sense that an alphabet made up of 24 images gradually replaces the old series of letters, with each image-letter holding for one second, which at today's projection speed means that it repeats itself 24 times." (Frieda Grafe)

PIERROT LE FOU (Jean-Luc Godard, France/Italy 1965, 10. & 16.11.). Neon writing, diary entries, letters, fragments of letters from large-sized signs, pages from books - Godard's treatment of writing and words in PIERROT LE FOU is similar to the more radical sections of his cinematic universe in its use of citation and fragmentation. A "fever dream" (JLG) which tells the story of a couple (Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo) in the form of an idiosyncratic homage to film noir who turn their back on Parisian society and set off on a thieving spree through the south of France. Their joint flight ends in betrayal, leading to revenge and death.

M – EINE STADT SUCHT EINEN MÖRDER (Fritz Lang, Germany 1931, 18. & 21.11.) The letter "M" written on a coat in chalk not only helps to expose the child murder in Lang's early sound film, but also provided the graphic leitmotiv for the film's marketing campaign. A letter as a means of creating recognition in two ways, flanked by the countless text inserts within the film: posters on advertising pillars, writing on the facades of buildings, and excerpts from newspapers give the impression of danger lurking everywhere and gradually intensify into an ever-growing hysteria of suspicion. Lang's suspenseful combination of thriller, gangster movie and psychodrama about the hunt for a sex offender is a multi-layered sociogram of Germany at the beginning of the 1930s.

POLIZEIBERICHT ÜBERFALL (Ernö Metzner, Germany 1928, 18. & 21.11.) Stretched and blurred so they can barely be read, the superimposed titles in the credits provide the prelude for this key fiction short of the German avant-garde about one day in the life of one man who gets hold of some cash which then becomes a hindrance.

THE PILLOW BOOK (Peter Greenaway, United Kingdom 1996, 19. & 25.11.) Greenaway's complex tale revolves around a young Japanese woman who covers her lovers' bodies in elaborate calligraphy and becomes entangled in a fatal revenge plot. The British director translates the idea of writing and characters as a "physical" system of perception with impressive visual opulence.

LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ? (Maurice Lemaître, France 1951, 20. & 30.11.) This landmark of Lettrist cinema was originally designed to be accompanied by interventions "This film must be projected under special conditions: on a screen of new shapes and material and with spectacular goings-on in the cinema lobby and theatre (disruptions, forced jostling, dialogues spoken aloud, confetti and gunshots aimed at the screen...)." (M.L.) Even without these performances, the film is radical: The director combines very different film scenes, editing in positive, negative and black film, damaged film material; he paints, embosses and scratches the filmstrips, displays text with alleged credits or warnings to the audience, insults directed at himself, collages or fragments of words. The soundtrack consists of a long monologue on which Lettrist poems are superimposed. The first screenings and performances ended in scandal - the film's impact on the Nouvelle Vague and today's avant-garde is beyond dispute.

STATCHKA (Strike, Sergei Eisenstein, USSR 1924, 24. & 28.11., with a live piano accompaniment by Eunice Martins) Even in his debut, Eisenstein was able to dynamically re-mold revolutionary material - a factory workers' strike in Tsarist Russia - into cinematic form. Some of the intertitles are also practically re-forged in the process, going from being imparters of information to becoming animated and moving themselves in a revolutionary manner.

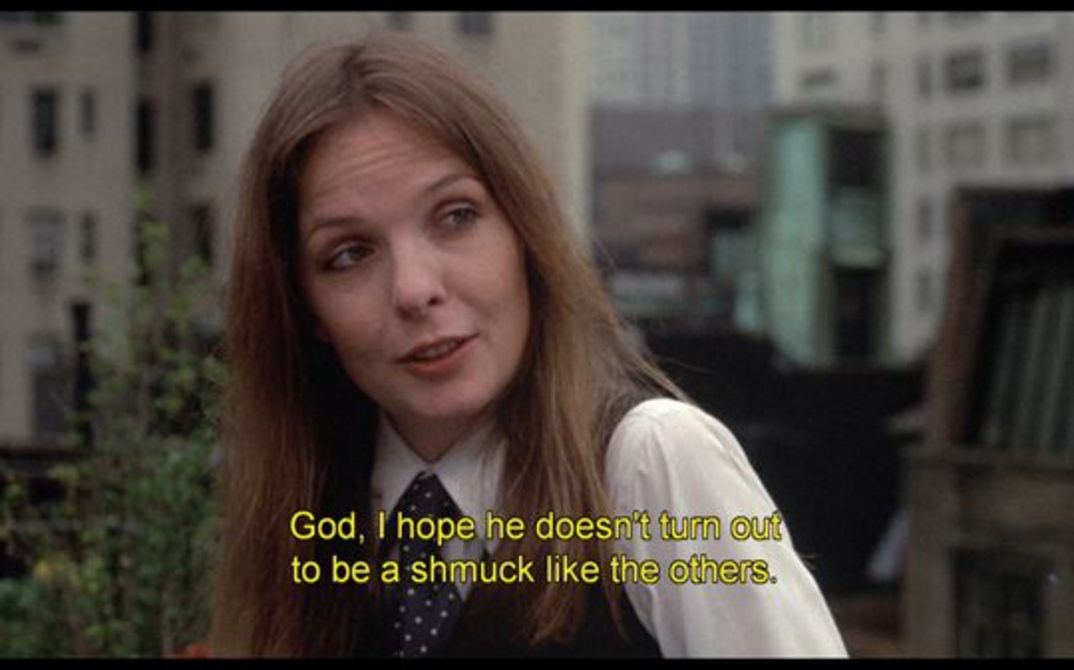

ANNIE HALL (Woody Allen, USA 1977, 23. & 27.11.) “Well, that's essentially how I feel about life - full of loneliness, and misery, and suffering, and unhappiness, and it's all over much too quickly” is how protagonist Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) sums things up, as the very embodiment of the archetypical New York intellectual. Alvy is in the midst of a crisis and musing on his past relationships. After two failed marriages and 15 years of psychoanalysis, he meets his big love Annie Hall, who ends up going her own way after a brief period of happy co-existence. Their courting and the start of their relationship takes is wracked with misunderstandings and self-doubt, including a dialogue that is supplemented with subtitles: they don’t translate from a different language as usual, but rather verbalize and visualize what the protagonists are thinking rather than saying. (mg/al)