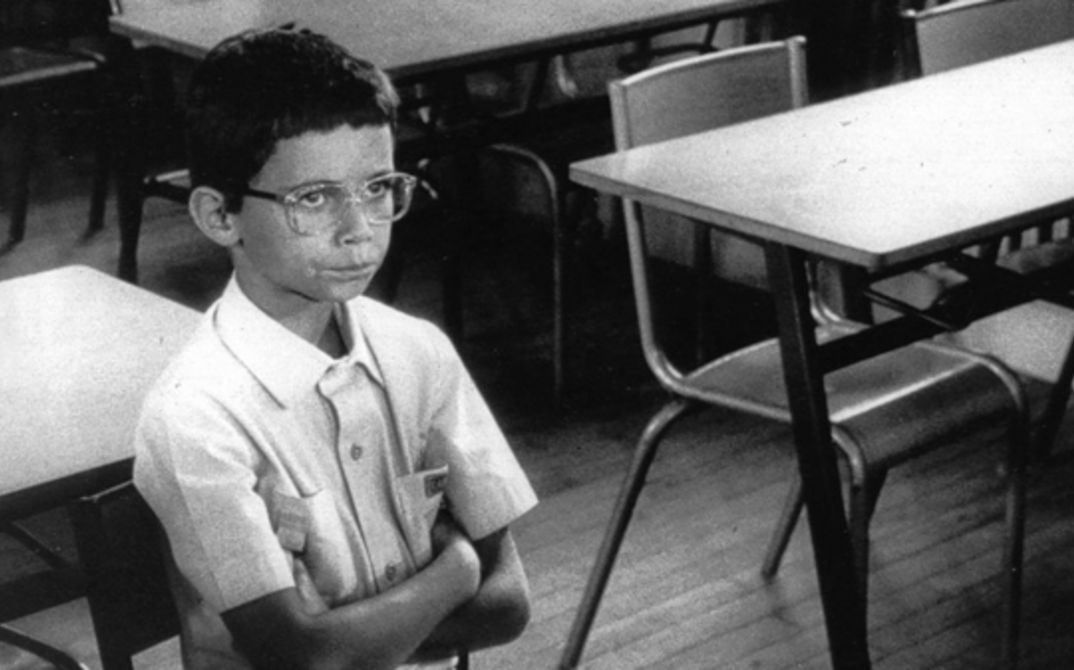

Why don’t you want to go to school?” is what a little boy called Ernesto is asked in Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s short film EN RACHÂCHANT. “They teach me things there I don’t know” is how he responds. His parents and his teacher at the desk at the front are baffled. Yet Ernesto knows that he will still grow up and make his way through life anyway.

How learning, school, university and the conditions according to which they all take place might be done differently is the question at the heart of the “Education Shock” exhibition at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (on until 11.7.), which describes a phase of upheaval and reorientation in the field during the 60s and 70s. The film program at Arsenal poses the same question and expands upon the exhibition, exploring the inhabitants of these old spaces and then their newer equivalents, as well as the stories and conflicts that play out in them.

Today’s societies have changed, particularly in Europe, to become immigration societies. Schools have received an additional central task accordingly: more than just being about conveying knowledge, they have become the places to decide whether children can become happy adults, how the society of the near future will be shaped, whether it succeeds or fails.

LA PYRAMIDE HUMAINE (The Human Pyramid, Jean Rouch, France/Cote d’Ivoire 1961, 6.7., with an introduction by Elena Meilicke) Jean Rouch gets the pupils at the Lycée Français in Abidjan to re-enact/act out a situation in which a girl newly arrived from France shakes up the previous structure of the class and make the difficult relationships between the local and French young people evident. The different levels of fiction and documentary form a game of sorts, which is reflected on by those acting, with director Jean Rouch also intervening again and again. Showing together with EN RACHÂCHANT (Danièle Huillet, Jean-Marie Straub, France 1982).

KARLA (Herrmann Zschoche, East Germany 1965, 8.7., with an introduction by Matthias Dell) A young, enthusiastic teacher (Jutta Hoffmann) starts her first job at a classical provincial gymnasium and takes on a “difficult” final year class on the university track. In this summer, the Socialist German Republic appears almost enchanted, with the tender hope for change and the genuine possibility of it almost seeming to hang in the air. But the 11th Plenum of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany decided on a radical change of course with regards to cultural policy. Of the 14 films produced that year by DEFA, twelve were banned and ended up in the cellar, including KARLA.

ICH BIN EIN ELEFANT, MADAME (Peter Zadek, West Germany 1969, 7.7., with an introduction by Claudia Lenssen) “One of the first great cinema soundtracks on street battles and student uprisings. In the hands of later theater icon Zadek, rebellion is blended with agitprop, cinétract, provocative comedy and gaudy Godard antics to form an anarchic firework display par excellence. Schoolboy Rull, as annoyed by the disguised Nazi teachers as by the pseudo-revolutionaries in his gymnasium, unleashes a grand-scale class struggle riot via swastika graffiti.” (Paul Poet)

IF … (Lindsay Anderson, GB 1968, 7.7.) about a revolt in a English boarding school shows the pressure for change in the ossified authoritarian British school system – and suggests drastic solutions when the rebelling pupils find an arsenal of weapons in the cellar. “Every image burns with a rage only able to be satisfied by imagining an apocalyptic coup that will overthrow everything important to the British middle classes.” (Jamie Russel)

PASSE TON BAC D’ABORD (Graduate First, Maurice Pialat, France 1978, 9.7., with an introduction by Rainer Knepperges) is about young people in the northern French provinces preparing to take their university-entry exams – or rather not preparing, as only few of them knew how things will go once they cross the threshold into adult life. The film accompanies them hanging out and observes their none-too-complicated conflicts: with their parents, about love and sex and having the right taste in music. One of Pialat’s great secrets, writes Glenn Kenny, is how looking directly at the banal can produce such rich, mysterious insights.

UN FILM DRAMATIQUE (A Dramatic Film, Eric Baudelaire, France 2019, 9.7.) follows PASSE TON BAC D’ABORD by jumping 40 years ahead – and asks the fundamental question: what’s it all about? Baudelaire gave a group of school children video cameras and entrusted them with the task of making a film about themselves. “The more the children get into filming, the more they gradually start to think. That a film can also analyze itself in elementary concepts in such fitting fashion is something truly seldom.” (Olga Baruk)

PLEMYA (The Tribe, Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy, Ukraine 2014, 10.7., with an introduction by Bert Rebhandl) A school in post-Soviet Ukraine as the edge of the abyss: teenager Serhiy enters a boarding school for the deaf and must prove his mettle in a world of nocturnal raids and forced prostitution. Not a single word is spoken in this film, which is not the only reason for its huge immersive power.

ELEPHANT (Gus Van Sant, USA 2003, 11.7., with an introduction by Christina Vagt) The floating, somnambulant camera follows the school children through long corridors in rooms flooded with light and across open campus landscapes, accompanied by subtle soundscapes by Hildegard Westerkamp. Immersion here too. The ideas of the school reformers and architects of the 70s all seem to have been implemented here, and the scenery only becomes threatening because we know that the film is based on the 1999 Columbine massacre, meaning we search for clues accordingly. Gus Van Sant denies obvious explanation in entirely deliberate fashion.

AT BERKELEY (Frederick Wiseman, USA 2013, 12.7.) If ELEPHANT explores surfaces, Frederick Wisemn dives deep into the spaces and structures of an elite university in the US. Wiseman’s way of throwing the audience directly into situations, frequently also into decision-making processes being carried out by the administration (such as in relation to tuition fees or the disadvantaged position of black students in how subject groups are put together), and neither adding dramatics nor cutting away fosters curiosity, intelligence, and patience.

SWAGGER (Olivier Babinet, France 2016, 13.7.) “Les Inrockuptibles” described Babinet’s film about young people in Aulnay-sous-Bois in the Paris banlieues as a “cinematic marvel”. They are far from being the victims of their parents’ biographies and the topography of their place of residence. They speak directly to camera and narrate, although not the whole time, and the question is always whether the film can still be regarded as a documentary. It makes repeated forays into fiction and gives its protagonists a considerable layer of glamour, although that’s perhaps the wrong word: swaggering is all about self-conscious cool.

PREMIÈRES SOLITUDES (Claire Simon, France 2018, 13.7., with an introduction by Esther Buss) What started out as documentary research for a fiction short developed into the intimate portrait of a school class from a Paris suburb over the course of the shoot. “Simon concentrates on the corridors, stairwells, benches and rooves of a French gymnasium, which become the locations for philosophical conversations between young people. They speak about financial worries, disease, loneliness, their parents’ divorces. Will we do it better than our parents?” (Anne Küper)

HERR BACHMANN UND SEINE KLASSE (Maria Speth, Germany 2021, 14.7., with guest Maria Speth) Stadtallendorf in Hesse, an industrial area. A school class with children who are not entirely sure if they belong here. They were born here, but find it difficult to feel at home in Germany. And Herr Bachmann, a teacher who never wanted to be a teacher – and soon no longer will be. The present, as well as a utopia. Cinéma vérité allemand. (lb)

The film series was curated by Ludger Blanke. In collaboration with the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Funded by the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.