Germany, 1992: Right wing extremist groups join forces to burn apartments housing asylum seekers and Vietnamese contract workers to the ground in Rostock-Lichtenhagen while police look on and citizens cheer. Two houses that are home to Turkish-German families are fire-bombed in Mölln, a small town in Schleswig-Holstein. Two years later, a Nigerian citizen named Kola Bankole is bound and gagged and subsequently dies of heart failure in Frankfurt while being deported. Two years earlier, Amadeu Antonio Kiowa, an Angolan contract worker, is murdered by neo-Nazis in his apartment in Eberswalde, a town in Brandenburg.

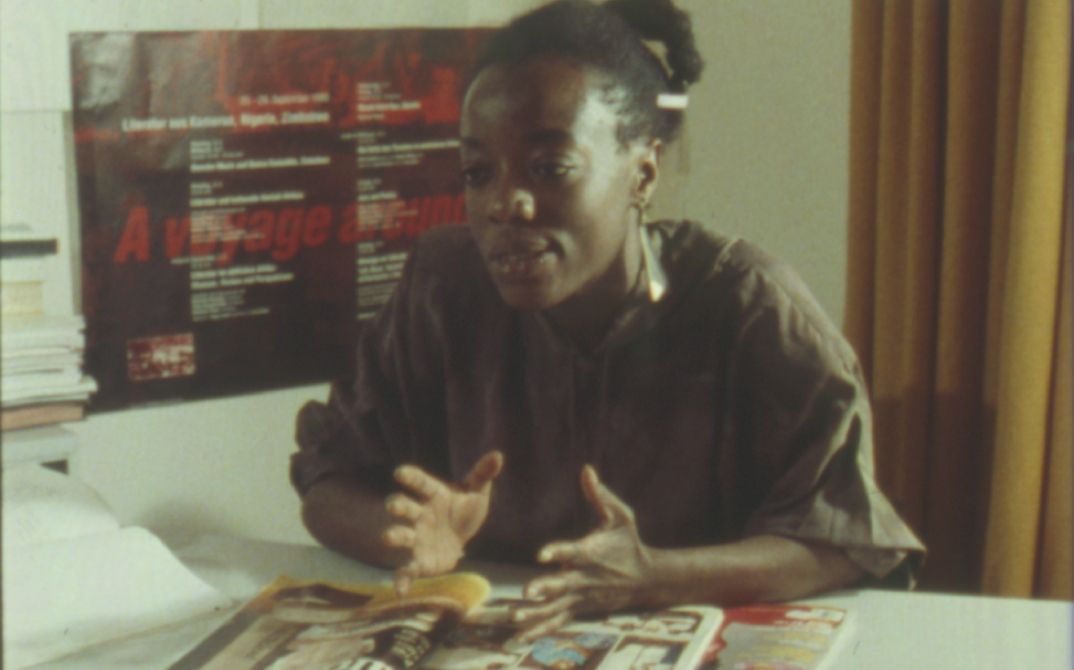

Two of the films in the Fiktionsbescheinigung programme were completed in 1992: BRUDERLAND IST ABGEBRANNT & BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD. They were made within the context of these and countless other examples of the structures of injustice that perpetuate a hostile situation for racialised people in Germany. In her film BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD (1992), Wanjuri Kinyanjui lays bare the racist conditions under which Black life survives and thrives in post-reunification Germany. Through dramatised scenes and interviews with Natalie Asfahaof the Initiative für Schwarze Menschen In Deutschland (ISD), fellow film student Tsitsi Dangarembga and various others, the documentary exposes experiences of structural discrimination and personal attacks suffered by different young Black individuals both born in and new to Germany. In BRUDERLAND IST ABGEBRANNT, Angelika Nguyen speaks to Vietnamese contract workers, many of whom have settled in Germany. It shows people on their last day in the country just before their forced removal, as well as those who have stayed but are still struggling to keep their families safe.

Ömer Alkın has written about the visibility the “Betroffenheit” documentary gives to diverse perspectives of history. Betroffenheitskino is a term often used pejoratively for cinema about or by people of colour. The term has been translated as “cinema of the affected” by Robert Burns, who associates this cinema with the 1981 essay, “Literatur der Betroffenen” (Literature of the Afflicted) written by Franco Biondi and Rafik Schami about an emerging form of literature penned by Turkish-Germans (“Gastarbeiter*innenliteratur”). Burns characterises these films as having a “social worker approach to ethnic relations. 1Rob Burns: “The Politics of Cultural Representation: Turkish–German Encounters.” German Politics 16, no. 3 (September 2007): 358–78, 132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644000701532718” The term has also been associated with a phrase coined by Cameron Bailey (director of the Toronto International Film Festival and founder of the festival’s seminal Planet Africa programme) to describe the approach of Black-Canadian filmmaker Jennifer Hodge De Silva, which speaks to "outsider and insider simultaneously" while appealing “to 'common sense' notions of injustice.” 2Cameron Bailey: “A Cinema of Duty: The Films of Jennifer Hodge de Silva.” The International Review of African American Art 10, no. 1 (1992): 51–59, 59.

Betroffenheitskino is often understood as aiming to explain the experiences of victims for the white centre. I would argue that these films are about more than just visibility or exposition. They present evidence to support concrete demands. These films certainly have a didactic relevance, but I believe the value of BRUDERLAND IST ABGEBRANNT and BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD goes way beyond that. These films perform an affective service. They are a call to arms for reparations, and this is what makes them so uncomfortable to watch.

I have argued elsewhere about film as witness to an affective debt. 3Karina Griffith: “Bankruptcy of Affect: Blackface in DIE UMZÜGE.” Darkmatter Hub (Beta), no. 15 (November 9, 2020). darkmatter-hub.pubpub.org/pub/tzi4q730/release/1. Affective debt is the sum of feelings owed for practices of prejudice. An affective debt is the result of the “the bad investment of white supremacy”; in addition to losing out on the talent and innovation that diversity provides, structures that have historically discriminated against Black people and p have held back on an entire archive of emotions. 4Idem. The feelings that are owed here go far beyond sympathy. It’s not about feeling bad for the protagonists in these documentaries – that would merely promote more white tears, which Robin Diangelo has warned us about. 5Robin DiAngelo and Michael Eric Dyson, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018).These films demand the kind of affects that prompt recognition and resolutions that actually seek to repair the structures of harm. In Why We Matter, Emilia Roig, head of the Centre for Intersectional Justice, outlines the important difference between sympathy and empathy and how this relates to images of racialised people in the media. She writes about the “empathy gap” (Empathielücke) that whiteness nurtures, citing film scholar Ann Everett’s study which shows that white people do not notice when a film does not have racialised characters but avoid films without white characters. 6Emilia Roig, Why We Matter. Das Ende der Unterdrückung, (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2021), p. 147–49. According to Roig, there is no in between – either you are for institutional change and actively working towards it or you are standing in the way. Sympathy keeps this situation at a distance, external to the person or institution offering it. Empathy is a feeling from the inside. It is an understanding that structures of discrimination have an impact on non-racialised people too. Empathy is knowing that there is no “outside” race, no way not to “see” skin colour, no post-racial playground.

In a talk at the Portland State University Library in 1975, Toni Morrison spoke about how a lack of empathy fuels capitalism. 7Toni Morrison, Portland State, “Black Studies Center Public Dialogue. Pt. 2” May 30, 1975. Portland State Library. Last accessed: September 4, 2019. https://soundcloud.com/portland-state-library/portland-state-black-studies-1After quoting from the general orders of Ulysses S. Grant and the letters of Theodor Roosevelt that went on to form the legislation for the inhuman treatment of Black and Jewish people in the USA, she recites a list of whippings and beatings recorded in the diary of William Byrd, a slaveholder in the 1700s. These accounts speak to the capitalist’s logic of discrimination – to try to convince people that they are inferior in order to exploit them. Morrison argues that “racism is distraction.” 8Idem. She warns against wasting time teaching the recalcitrant about the basics of bigotry. When whiteness wilfully fails kindergarten-level critical race theory, it is by design. Morrison ultimately issues the following warning while also offering a chance for discussion:

“You don’t waste your energy fighting the fever; you must only fight the disease. And the disease is not racism. It is greed and the struggle for power. I urge you to be careful. For there is a deadly prison: the prison that is erected when one spends one’s life fighting phantoms, concentrating on myths, and explaining over and over to the conqueror your language, your lifestyle, your history, your habits. And you don’t have to do it anymore. You can go ahead and talk straight to me.” 9Idem.

When artists talk straight to Toni Morrison, they speak on a level of intimate knowing. There is no concern about whether the work will sell or if it will offend. Morrison asserts that artists are the best people suited to talk about racism, because they concentrate on “the names of people, not only the number that arrived.” 10Idem. It is exactly this specificity that is lost when films that deal with the topic of inequality are seen simply as documents and not pieces of art. The problem with labelling films that demand affective reparation as “films about racism” is that they are discussed only in that context. This precludes a deeper discussion of the aesthetics, the textual and formal beauty and artistry of these films.

Both BRUDERLAND IST ABGEBRANNT and BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD punctuate their respective testimonies of violence and discrimination with particular scenes that employ specific stylistic means. As Isaac Julien insists, artists must rewrite the technologies of representation to create an “aesthetic of reparations.” 11Isaac Julien, and Brendan Wattenberg, The Pleasure of the Image: A Conversation with Isaac Julien, April 29, 2016. Last accessed: May 13, 2021. https://aperture.org/editorial/pleasure-image-conversation-isaac-julien/. Nguyen and Kinyanjui’s aesthetics represent an affective level of memory. Their respective styles of storytelling harken both back in time and forward to the future in such a way as to situate their witnesses outside of total victimisation. BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD places different visual motifs throughout the documentary that form a subtle counter-narrative to the story of suffering of the African and European protagonists. These include books about African history, culture and civilisation on a plain background, uncommented and unnarrated. Each image is emblematic and iconic. One might read these images in speculative fashion as calling into being the Each One Teach One eV. (EOTO) Black library founded in 2012. In fact, EOTO is located in the same district of the city where Kinyanjui shot the dramatised scenes of racial violence at the start of the film: Berlin, Wedding. The empowerment space EOTO started as a collection of books and a dream – the passion project of Vera Heyer in the early 1990s. 12Michael Götting, “Turning One’s Attention to Knowledge.” Latitude, Goethe Institute (blog), October 2020. Last accessed: May 13, 2021 https://www.goethe.de/prj/lat/en/ide/22005978.html. Even the binder of magazine clippings featuring xenophobic images in the film is reminiscent of EOTO’s current community-led archive project: Sankofa BRD / Sankofa DDR. The books in Kinyanjui’s film thus point to another epistemology, one that is Black-authored and classic.

Nguyen’s film juxtaposes standard interviews in intimate spaces with cinéma vérité video sequences of Vietnamese workers in their last moments at Schoenfeld airport. The fluid camera and confident hand-held shots make these abrupt moments of departure unforgettable. The camera seems to be eavesdropping on a moment of stillness in post-reunification Germany. The airport is transformed into an extension of the state apparatus. The collapsible tables in the departure hall reconstruct the space into both a bank and an immigration office, as the workers have their passports returned to them and are given their final pay. The calm, cinematographic treatment of these scenes adds a layer of additional distinction and respectful distance to the sensitive narrative. As Nguyen states in an interview with Polly Yim, it was important to get away from a “paternalistic” way of telling the stories of migrants. 13Angelika Nyugen and Polly Yim. “Brennendes Land.” Contemporary &, October 2019. https://www.contemporaryand.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/C_Another89_web_lowres.pdf. The perceptive camerawork in the airport scenes takes the protagonists out of the flatness of victimisation and into the deep focus of a complex and more courageous story.

Returning again to 1992, the German dubbed version of the Christmas film HOME ALONE 2: LOST IN NEW YORK, which was released that same year, portrayed Kevin and his siblings using pejoratives and racist slurs that would be unthinkable in the original US version. In 2020, German actress Thelma Buabeng (Tell Me Nothing From The Horse) compared the German and the English versions of the family movie via split screen on her Facebook page. The derogatory words were not present in the original. Netflix responded by saying this version will be changed by Christmas 2021. Buabeng asserted that it is not her job to point out racism in how films are dubbed into German (“Ich bin nicht die Synchron-Polizei”). She rejects the idea as a distraction – calling out bad behaviour is not her responsibility. Racism is a distraction when it is made the main attraction, whereby the mere act of talking about the problem is wrapped up in a bow and presented as a solution. Biased structures like to flatten us, to simplify us and put us in boxes that serve the purpose of keeping us busy telling the biased structures what they already know.

BRUDERLAND IST ABGEBRANNT, BLACK IN THE WESTERN WORLD and all the films in this programme beg a response beyond applause, tears or a pat on the back for those who dug them out of the archive and put them on display. These films bear witness to both the experience of bias as well as to the ingenuity and strength of the Black and POC artists and filmmakers who made them. They don’t just show, they testify to the affective debt accrued by structural and interpersonal discrimination. They demand emotions that promote swift, appropriate and sensitive measures to rectify and repair institutional hinderances that force peoples of colour into precarious and disadvantaged positions that keep us not only from making films, but from making all types of contribution for lack of opportunity. And they do it beautifully, reflecting an aesthetic of reparations in German cinema. Films about anti-Blackness and bigotry are the receipts of an affective debt, proof of paid affective labour and incredible patience with petulance. But we didn’t programme these films to lecture audiences about things that German society already knows and owes. There is no didactic ulterior motive.

We programmed these films because they talk straight to us.